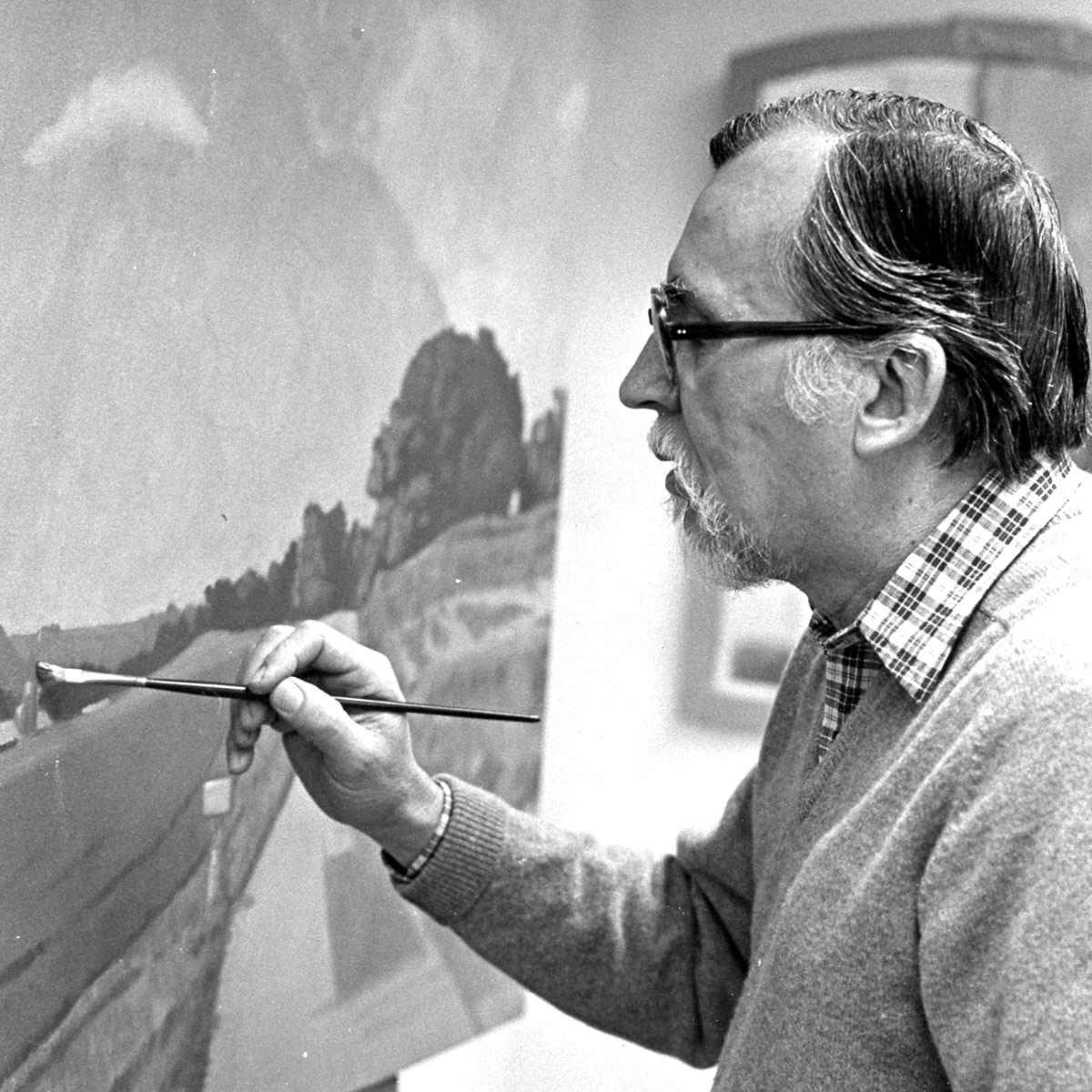

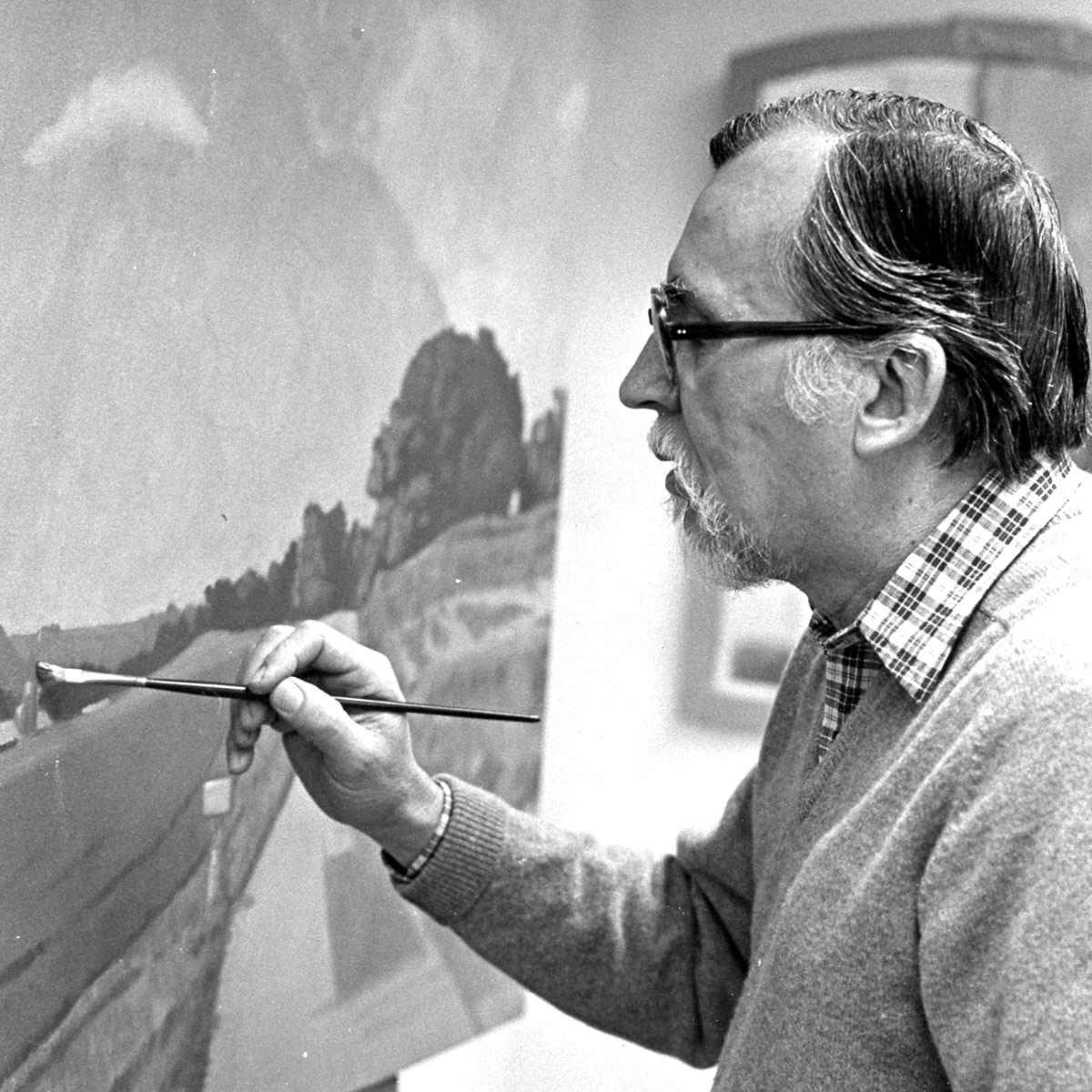

Mr. Gibson Byrd by Gallery Of Wisconsin Art, LLC

| City: | Not Available |

|---|---|

| State/Province: | Not Available |

| Country: | Not Available |

Description

BORN: February 1, 1923 in Tulsa, OK

DIED: April 16, 2002 in Del Mar, CA

A long-term member of the UW-Madison Art Department, D. Gibson Byrd (1923-2002) was a figurative and landscape painter, and a master of coloristic subtleties and atmospheric effects. Art critic James Auer stated he was “a leading Wisconsin artist for 35 years” (WSJ 2002 Obituary). Byrd’s interest in figurative painting started in the early 1950s, and this work emphasized social realism, angst and banality in the twentieth century, and auto-biographical fantasy. Around 1980, Byrd turned away from a narrative, psychological approach, focusing his attention on rural landscapes, particularly in southern Wisconsin and coastal southern California where he retired to in 1991. His strong feel for the land was partly derived from his Indian heritage (his grandmother was a Shawnee Indian and he was a qualified member of the Shawnee Tribe). Although best known as an oil painter, he also worked in the mediums of gouache, pastel, and charcoal.

Byrd was raised in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and after high school worked as a draftsman for two years before serving as a B-17 engineer/top turret gunner during WWII. After receiving a B.A. in Art from the University of Tulsa in 1949, and his M.A. of Fine Arts from the University of Iowa in 1950, he taught high school art in Tulsa. From 1952-1955 he was Director of the Kalamazoo Art Center, and lectured at the University of Michigan Extension Division. He joined the UW-Madison faculty in 1955, taught until retiring in 1985, and then was Professor Emeritus until 2002. His Wisconsin art legacy can be seen through his contribution as an educator, mentor and an advocate for the arts within the community; and his artistic achievements, especially his focus on social fairness and justice and his enduring depictions of Wisconsin landscapes.

An artist-observer, Byrd’s work explored human loneliness and isolation, frequently provided social commentary, showcased social fairness and justice, and often lampooned the status quo and materialism. “His subject matter is very much of our time: anomie and alienation, military service and domesticity, flashy commercialism and enduring values; the interrelationship between the artifact and natural environment and formal invention” (Auer 1988, Retrospective Catalog). Byrd’s work in the 1950s reflected an interest in interiors and everyday life. By 1962, he was increasingly concerned about the implications of his Shawnee Indian ancestry, a topic he returned through throughout his life and explored through social commentary that emphasized racial bias, and the national struggle for equality. In the early 1970s, Byrd shifted inward working autobiographically exploring life stages, including a haunting series focused on his childhood home where his dad and older brother passed away. Subsequently, he painted spartan and geometric interiors, often populated with strange assortments of figures, animate and inanimate, clad and unclad, conveying a perceptible aura of unease.

Then he shifted to painting rural landscapes in 1979, soon after being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. These elaborately layered, and richly evocative scenes often had atypical lighting conditions, with highlighted rear-lit trees, shadows cast by the rise and set of the sun and moon, and rare violet haze. They also reveal a mastery of implied perspective, defining nuances of distance through glowing planes of subtly differentiated color, often vibrating with deep and complex emotion (see two examples). This remarkable shift to landscapes in his mid-50s while dealing with a physically-debilitating disease was extremely well-received by critics and collectors, and his shows during this productive decade regularly sold out.

A common theme in reviews of his exhibits (including his 1988 and 2008 retrospectives) was surprise and disappointment that his work is not as well-recognized nationally as it should be. Byrd’s willingness to explore and change topics and approaches has in some ways defied placing him in a single category, perhaps lessoning his recognition and appreciation of the full body of his work. His lack of interest in self-promotion (a trait consistent with his upbringing) also contributed to the situation. Throughout his career, however, Byrd delighted followers with his essential unpredictability, willingness to explore new subjects, and challenge himself even while dealing with a debilitative disease.

Byrd’s paintings were frequently exhibited nationally in competitive, invitation, and one-person exhibits from 1949-1991 throughout the greater Midwest, and most extensively in Wisconsin. His work has been periodically exhibited since then, including a 2008 retrospective (Dean Jensen Gallery, Milwaukee), and a spring 2020 Shawnee Tribe Cultural Center, Miami Oklahoma one-person show. His art is part of public collections in more than two dozen institutions throughout the US, and particularly well-represented in Wisconsin.

In the early 1980s Byrd turned away from a narrative, psychological approach and focused his attention on the rural landscape. These landscapes focused on rural southern Wisconsin landscapes with simplified shapes using softly layered colors. His strong feel for the land was in part derived from his Shawnee Indian heritage. Although best known as an oil painter, he also worked in the mediums of gouache and pastel.

He was a member of the University of Wisconsin for 30 years, when, in fragile health from the effects of Parkinson’s disease, he retired from teaching and moved with his wife Benita to California.

SOURCES AND BIOGRAPHICAL EXCERPTS: